The Trans Women Helping Trans Immigrants

The transgender population is a very small facet of our society. With that many of them are in positions that put them in the least favorable parts of society. According to UCLA’s Williams Institute estimates of the country’s population: 700,000, or about 0.3 percent of adults identify as transgender. That number only represents the number of transgender individuals who are American. However, there is no data about how many immigrants are in America who identify as transgender. With the help of social programs, these individuals can find resources that they need to survive.

Leslie Frias sitting at her desk in Bienestar in Hollywood, Calif. on March 22, 2017.

Entering through the dark draped doors, she gracefully saunters across the room. One can tell she has perfected the art of a sultry sway and flaunts it throughout her elegant movements. Her confidence radiates out as she guides her group in sessions. She doesn’t hesitate to keep her groups on topic or discussing the matters at hand.

Leslie Frias doesn’t have a story like most transgender immigrants. She was lucky to be offered employment in the U.S. on a work visa when she was discovered in Tijuana performing drag.

After coming to Los Angeles, Frias entered the Bienestar pageant in 2009. She won the crown to become queen. After working the year of volunteer community service, Bienestar offered her a position in the organization helping the trans community. She hasn’t stopped since.

Frias says Bienestar is the starting point for many of the trans women who’ve gotten into social justice and want to help other trans individuals.

“Bienestar has operated for over 25 years,” Frias says. “In September, we’re celebrating the 20th year of the transgender program. Both Mariana Marroquin and Bamby Salcedo started here. They were here when I started. We all still work together.”

Frias reveals Bienestar offers multiple programs in LA for the trans community. She explains they have testing for HIV, free mental health, support groups, access to medication and how to find opportunities.

Frias is the head locator and head community organizer for Bienestar. She makes sure the trans community gets the information to stay safe.

“We teach them how to deal with harassment, the police and other issues that may come up in their lives,” Frias said. “We teach them they have to make reports because it is going to make a big difference. We’re working with the LAPD to help that process.”

“I am a fighter; I am a rebel.”

– Leslie Frias

Frias declares while the trans community has grown so much over the years, it is still put on the back burner.

“We still don’t have much,” Frias says. “Even though we have a big voice, we’re in the media, have famous people, it doesn’t make a difference. We’re still not seen.”

Frias states many of the trans individuals she works with are foreigners with many issues.

“Most of the girls are immigrants,” Frias says. “They struggle with language, money, and most don’t have the opportunities for regular jobs so they turn to sex work. We help them with better opportunities and legalization, but when the opportunities are presented to them, most aren’t ready. I don’t know why.”

Frias says many of the trans women are in shock over the new immigration policies proposed.

“Multiple girls are in the system,” Frias says. “We have a few girls that just came out of the detention centers. They are fighting. They talk about their histories and their treatment inside those places. They all suffer badly.”

Though Frias says she has no experience of what most of these girls suffered, she tries to understand.

“When I hear these stories, I feel bad, but they aren’t my stories,” Frias says. “I can’t speak for them. Every case is different. Everyone is different. Not everyone is lucky like me.”

Frias says the hardest part of her job is teaching the girls to break the misconceptions of what trans is.

“One of the big issues is culture, religion, and stigma,” Frias says. “In these sessions, we talk about safe sex and how to be healthy to prevent the spreading of HIV.”

Frias believes the trans community has always been strong.

“We’re fighters,” Frias says. “We’re always fighting for something new, for our ideas or with bullies who make us feel uncomfortable. Immigration isn’t the sum of all their problems, only a part. We should be aware and ready to fight. I am a fighter; I am a rebel.

Frias says her accomplishments include living with HIV for over 19 years.

“One of my passions is helping the girls,” Frias says. “I have the opportunity to work with them. I’m trying to help fix their lives by focusing on prevention and the right tools to stay healthy. I’m undetectable with my illness and people don’t understand what that is. It is one of my jobs to talk about it and I bring it to the table as if it was normal conversation.”

For the future of her programs, Frias hopes to see less infection in the Latino community and other communities too. She believes they all deserve the rights to thrive.

“Numerous transgender women don’t have access to health care which is more than treating illness, but hormones, mental health, and testing,” Frias says. “If they aren’t being healthy, they aren’t being safe.”

Frias wants to keep serving the trans community until she retires.

“This work makes me happy,” Frias says. “I want to keep working for transgender rights. I want to speak for my rights and for those who don’t have these rights. When I’m done, I can be at peace with happiness.”

Mariana Marroquin at her destk at the Youth Los Angeles LGBT Center in Hollywood, Calif. on April 7, 2017.

Standing at 5 feet 7 inches, she doesn’t stand out amongst the group of trans women she is leading, but when she speaks, everyone listens. She teaches classes at Bienestar to the trans individuals on dealing with violence and other issues of harassment. Her voice is soft, but her message is strong.

Mariana Marroquin is the Anti-Violence Project manager and a client advocate for the Los Angeles LGBT Center.

Marroquin believes LA is one of the places many trans individuals try to get to when seeking asylum.

“Los Angeles has many organizations that work with trans people,” she says. “There are many wanting to come here because of these programs and the big community. It’s the destination in mind when they head to cross the border.”

As a client advocate, Marroquin works with immigrants seeking to stay here legally. Sometimes that means having to bring up harsh pasts.

“In this department, we work with many trans women looking for asylum,” Marroquin says. “They have to go through layers of painful memories repeatedly through the process. It is very traumatic.”

Marroquin wishes it was easier for these individuals to get the help they need, but the immigration process can be long and grueling. She highlighted it can take up to four years to be seen by a judge, so she helps them promptly.

“As soon as they walk into my office, I let them know they can be themselves and they’re in a safe space,” she says. “Then we start the conversation. We talk about what they survived and how they finally made it over here. Then, how they must fight their cases.

“To relive all of those memories, layers and layers of violence, child sexual abuse and what they experienced crossing Mexico is rough. A majority of our clients that we work with are from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. So, by the time they get here, they have already been immigrants. So being with a different accent, and being LGBT in Mexico is adding another layer.”

Marroquin relates personally to how many of these trans individuals feel.

“I went through the same process and seeing myself as a victim one more time, it was something I didn’t want to bring back,” Marroquin says. “For asylum seekers, they must bring it up multiple times: in front of me, another coworker and an attorney to see if they want to take the case. They have to go to court where they have to keep bringing it up, details of when it happened, and with who.”

Marroquin says when she was applying for asylum people in her country were being murdered.

“I applied for asylum coming from Guatemala,” Marroquin says. “At the time I left my country, I was getting away from the violence. The government decided to do social cleans. They were killing all the people who looked different. About the time I left more than 27 trans women were killed that year. It was 1998.”

Marroquin shares what her experiences are working with her clients.

“Something many of the clients seeking asylum have is courage,” she says. “They go through so much they get to the point of having nothing to lose. They risked everything to get here. I feel their resiliency as they continue to survive.

“But I have also noticed there’s much sadness because they have to leave their homes, their countries, their languages, and their cultures. Knowing you’re always going to be an outsider to this land is hard, even without being transgender. Although their biggest fears are trying to figure out how to make it in the U.S. There aren’t many resources for trans immigrants and for the ones who don’t know how to access our resources, they aren’t sure about their futures.”

Marroquin says the resources trans individuals can receive from the LGBT Center include medical access, hormones, legal services, support groups and housing for trans youth under the age of 24.

Marroquin explains how easy it is to get involved in the street economy.

“It’s tough to find a job right away,” she says. “Sadly, that’s why sex work is an option. When you’re coming from rejection and persecution, finding someone out there who is willing to pay to be with you and validate you, it can be kind of attractive. Over there they want to kill you, call you names and here is someone who’s like, ‘I see you, I’m attracted to you and I’m going to give you something in exchange.’”

“I think for trans people, the American dream doesn’t exist.”

– Mariana Maroquin

Marroquin says that she feels lucky to be in her position.

“For someone who has suffered trauma, for someone who has suffered being persecuted, I think it’s empowering when someone tells you can do something and that you can be someone for someone else. I think it’s something powerful for a transgender woman, who is an immigrant, to know that they have the opportunity to help others.

“It has been 16 years since I have started at a nonprofit. I now manage the Anti-Violence Project, I manage staff and I represent this program with not only helping trans people but also the LGB and victims of hate and violence. Getting this opportunity, I think that is why every time I get the chance, I talk about what it means to give someone an opportunity to succeed.”

Marroquin has experienced one event in which a trans woman was deported while she was doing advocacy.

“Eight years ago, I was working on an outreach project downtown,” she says. “I met this girl doing sex work in the area. We were making this documentary, “Wild Dance”, at a club called Silver Platter. She was one of the participants and she was deported back to Guatemala.”

Marroquin stopped to take a deep breath before trying to continue with what she was saying. Before she spoke she let out a long sigh.

“We had her video where she was talking about how she was happy to be here and happy to be herself. Then a week after we find out she was deported,” Marroquin says slowly.

Marroquin says it’s hard for trans individuals to find community once they come here because many of the neighborhoods they would hope to find welcoming aren’t.

“When coming here from Latin America, you’re going to find different groups and neighborhoods where many people are still not open to respecting your rights,” she says. “Even though these trans individuals are in the United States, they get surprised when they get a job, that people still harass them, ask them inappropriate questions or call them names. That’s the reality over here.”

Marroquin hopes to one day see the trans community accepted for who they are, without any prejudice.

“I think for trans people, the American dream doesn’t exist,” Marroquin says. “It is about surviving, it isn’t about dreaming, but surviving. Being able to be in a place where you can breathe, where you can come out during the daytime and be yourself. That doesn’t fully exist yet.”

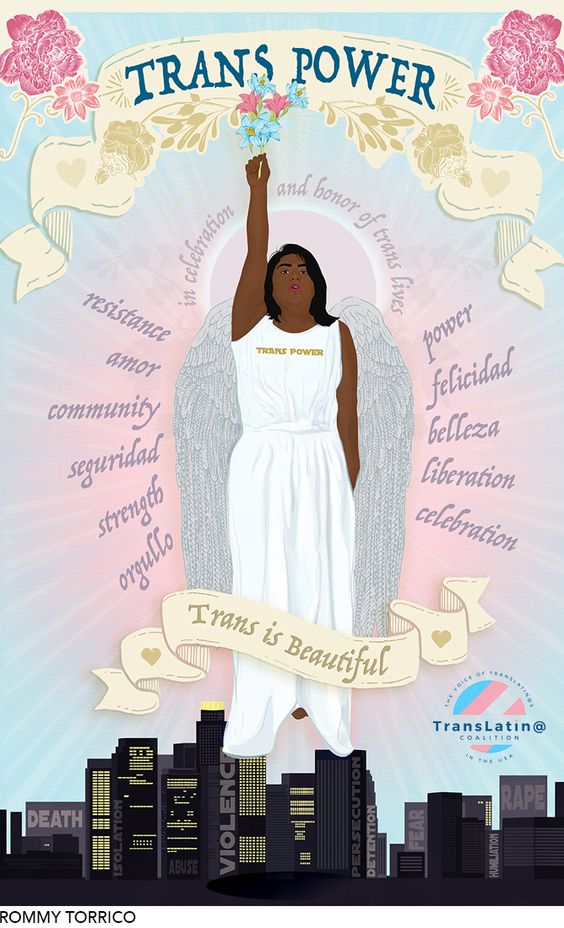

Salcedo standing in front of The Trans Power poster in the TransLatin@ community room in Los Angeles, Calif. on April, 21, 2017.

With her short, shaggy, bleach blonde pixie cut, she enters the waiting room with authority. Quickly glancing over the faces, she recognizes a trans woman whom she is familiar with and embraces her with a warm inviting smile. She finds time to catch up and asks the woman about her circumstances.

Their conversation turns sour as the woman admits she is having difficulty with her housing and that she hasn’t been at her best. Without hesitation, the blonde moves into action listing resources to the woman in which she can turn to so she can get her situation back in control.

With those actions, one can see Bamby Salcedo is knowledgeable and committed to what she does.

Salcedo is president of TransLatina Coalition, an organization she has helped establish that addresses the institutional challenges which are pressing the trans community when there aren’t many programs dealing these issues.

“Most of the work is policy and advocacy related,” Salcedo says. “We want to change the structures that have marginalized us. We’re doing work no one else is doing. We’re the first drop in center for trans people. We’re the first trans organization providing direct services and trans related advocacy.”

Salcedo says the TransLatina Coalition has operated for a year and three months. Sinc it has expanded to five paid staff positions and served more than 60 trans individuals. One of their current successful programs is providing free lunch to trans individuals who stop by to eat.

Salcedo is familiar with the experiences of the individuals she is assisting as she grew up in their same conditions.

“My story is like the people I work to help,” Salcedo says. “I was involved in the street economy with drugs, sex work, and homelessness. I was institutionalized at 12, I was in prison, I was in the immigration detention centers, I was deported. You name it, I lived it.

“I always say I’m one of the chosen few, that I got this opportunity to transform my life and can support those who are still living this struggle. When I came to Los Angeles, it was everything I wanted. It was also the place I came to be myself and where I started my transition. Back then there were no services, just the streets.”

“The talk about building the wall; the wall has been built.”

– Bamby Salcedo

After getting into a treatment program Salcedo became involved in social justice. Years of working at different organizations, and starting several different organizations of her own, Salcedo says she feels pride for what is to come for her current organization.

“I want the ability to open opportunities for other people,” Salcedo says. “We have the power as individuals and as a community to accomplish whatever we want. I always say I’m a piece of the puzzle. We’re all an organization.”

With the new immigration policies being set, Salcedo points towards past U.S. history to highlight this isn’t the first war on immigrants. She explains the Latino community was attacked before in the 1920s and early 1990s.

“What’s important is we understand we’re resilient communities that can obviously continue to persist and fight the good fight. Most importantly, it’s important we understand and recognize the importance of organizing. If we can do that then we’re able to fight the power. It’s just a matter of being strategic, being able to say fuck you and do whatever we need to do.”

Salcedo describes the situation and struggles that undocumented trans people have.

“Crossing the border is hard right now,” she says. “The talk about building the wall; the wall has already been built. I think current immigration policies and the immigration administration are going to make it harder for people to seek asylum or seek refuge. Most people who are trans come to this country to run away from violence and persecution.”

Salcedo professes being in this line of occupation is difficult, tiring and demanding.

“Doing this kind of work isn’t easy and it’s not for everybody,” she says. “You want to stand up to those challenges to say yes or no and the ability to call out the injustices when they’re there. If you don’t take care of yourself, you’re not going to be able to do what you’re supposed to do.”

Salcedo says she is working with other groups to bring as much support as she can to the trans community.

“We’re all a part of a coalition that’s helping people get support, such as legal services,” she says. “In fact, there is a coalition of different legal entities and nonprofit organizations that are part of it. The work we do with the LGBT Center and ACLU is mostly to get people the right legal help.”

Salcedo is ready to tackle the new changes coming to social services.

“With the budget that was presented, services for our people are the first ones to go,” Salcedo says. “That is one thing in the back of my mind. This is a challenge and I’m up for the challenge. I’m going to do my best to keep the doors open, to make sure we continue to provide the services we’re providing, but also to continue to expand because those services aren’t the only needs our community has.”